The first in a series of interviews with TidalCycles people.

As I remember you started out with the 365 tidal patterns project, the first major foray into Tidal aside from myself. It must have been quite an ordeal getting tidal installed as an early adopter, can you remember what drew you in and made you put the work in?

The soul of Tidal is rhythm and patterns, and as a percussionist/drummer (and programmer) this really resonated with me. In fact, this might be the most important reason why I was so intrigued with Tidal. In Tidal, I saw ways to create very complex rhythms that could evolve and change over time; I would make a pattern with small amounts of code that would take minutes to cycle until repeating. As a music producer who liked to create complex drum rhythms, Tidal looked like endless fun!

But I think the reason I really got drawn in was because I realized I could use this type of music-making for more than just at-home fun. I really wanted to get good enough at Tidal so that I could get out and perform with it.

I remember the date I installed it: December 5th 2013: https://github.com/tidalcycles/Tidal/issues/6

The installation process wasn’t too bad, but I knew it would be worth the wait and effort whatever time it took. I think I spent a couple of afternoons trying to get it to work. I had some prior Linux experience, and compiling classic Dirt wasn’t too bad. Linux audio and Jack were new to me though; I think that’s where most of my initial struggles came from. I also hadn’t used Emacs before, and Emacs was the best-supported editor at that time. It took some time to get the Emacs configuration correct. It definitely required a lot of trial and error with Jack and the Emacs config.

What ‘strategies’ have you developed/collected for using Tidal? e.g. combinations of functions you like to use together, particular ways you like to twist patterns etc. Feel free to share particular examples! How important are these strategies to you? I think you’ve defined a few of your own functions. Could you share some details? How has this gone as an otherwise non-Haskell programmer?

There are so many…

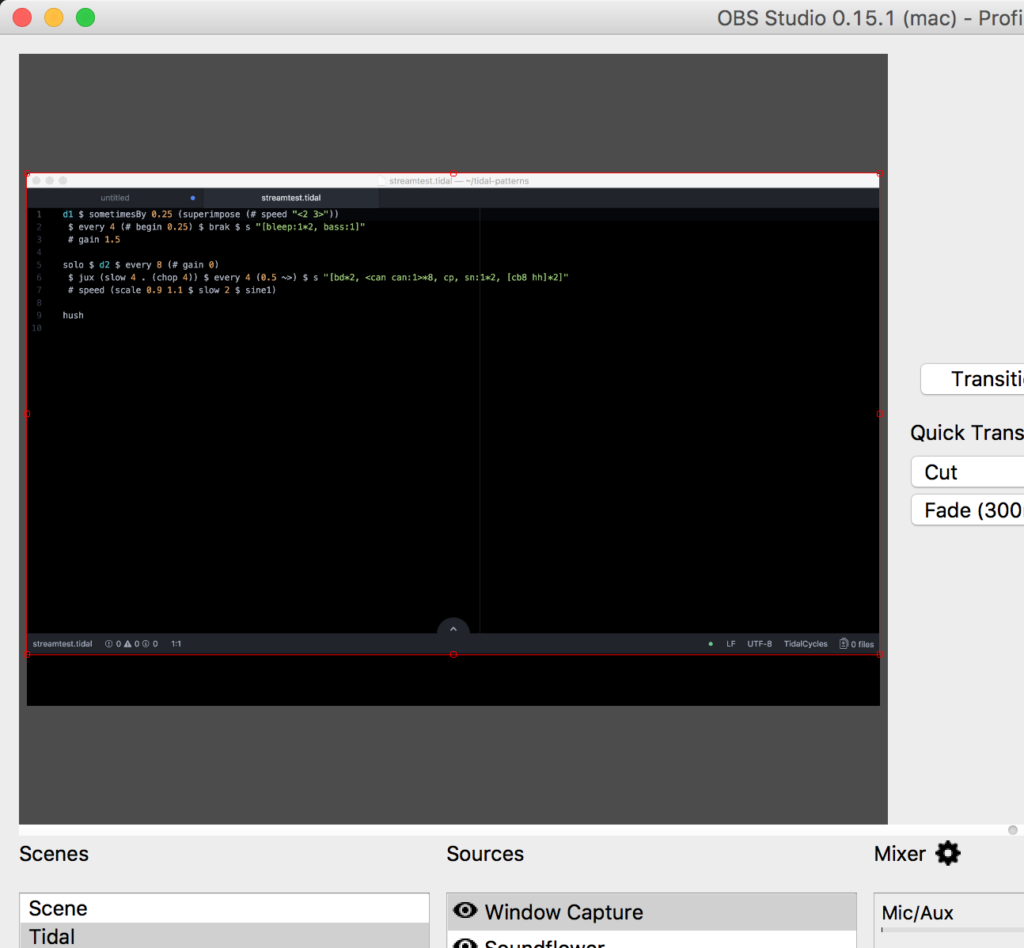

First, there’s the `stack`.

When I was working on 365 Tidal Patterns, I imposed a constraint that I had to put the pattern on a single line. Then I relaxed that constraint to only using one Dirt connection (e.g. `d1`). This is where I discovered I could use `stack` to create layers of patterns on one Dirt connection. From the start I think I’ve always been a fan of using a big `stack` to create layers of stuff:

d1 $ stack [

sound "bd(3,8)",

(0.5 <~) $ sound "cp",

every 2 (density 2) $ (0.25 <~) $ sound "arpy*2" ]

The great benefit of the stack is you have two levels of transformation: one at the pattern level and one at the stack level. The pattern above has transformations at the pattern level (e.g. `(0.5 <~)`). Here is a pattern with transformations at the stack level:

d1 $ every 3 (rev) $ every 4 (chop 4) $ stack [

sound "bd(3,8)",

(0.5 <~) $ sound "cp",

every 2 (density 2) $ (0.25 <~) $ sound "arpy*2" ]

Next, there’s moving time around. Early on when learning Tidal I started to do this a lot:

every 3 (0.25 <~) $ every 4 (0.25 <~) $ sound "..."

I then attempted to author my first Haskell function in Tidal to make this a first-class capability in Tidal. We called it `foldEvery`. My implementation didn’t work, and I think Ben Gold actually implemented the final version. It’s used like this:

foldEvery [3,4] (0.25 <~) $ sound "..."

Another really common thing I like to do is use different audio effects and transformations on different cycles to create constant variation in patterns:

d1 $ every 3 (0.5 <~) $

every 4 (chop 4) $

every 5 (# speed "1.5 -1 0.5") $

every 6 (# crush (scale 3 8 $ slow 2 tri)) $

every 7 (rev) $

stack [ sound "bd(3,8)", sound "cp*2" ]

I think that pattern will cycle 420 times before repeating. 420!!! With such little code you can get so much continuous variation. This never ceases to excite!

Another feature of Tidal that I exploit a lot is the polymeter syntax:

d1 $ sound "{bd ~ ~ bd ~}%4"

d2 $ sound "ch*8"

The above `d1` pattern will play “in five” while the `d2` plays in a regular division of eight (or four, depending on how you feel it). I love this type of rhythmic interplay: two patterns with the same pulse but different lengths. My favorite band when I was young was Helmet, and they did this type of thing all the time (drums in “four” while the guitars were in five, six, or some other division of time).

Another technique is to define a common rhythm for multiple patterns to use:

let pat = "{1 ~ ~ 1 ~ 1*1 1 ~ ~ 1 1}%8"

d1 $ gain (pat) # s "bd"

d2 $ gain (pat) # s "arpy"

And as an added bonus, put that code in a `do` block so that you can change the rhythm and have all patterns take on the new rhythm at the same time:

do

let pat = "{1 ~ ~ 1 ~ 1*1 1 ~ ~ 1 1}%8"

d1 $ gain (pat) # s "bd"

d2 $ gain (pat) # s "arpy"

As far as my own custom functions, I have defined many. Perhaps my favorite is one I call `rip`:

let rip a b p = within (0.25, 0.75) (slow 2 . rev . stut 8 a b) p

Which creates a sort of quick, backwards, rush effect.

I also use a custom function called `brakk` to time-stretch and create random drum breaks from pre-sliced break loops:

let brakk samps = ((|=| unit "c") . (|=| speed "8")) $ sound (samples samps (irand 30))

As a non-Haskell programmer, creating these types of shortcut functions is pretty easy because they just re-use existing common Tidal functions. It’s just like writing regular Tidal code, except you have to know how to give a function a name and express what parameters it will take. In contrast, I am not very good at lower-level Tidal functions or common Haskell language features to create new capabilities within Tidal.

Or to phrase that question another way, what parts of tidal do you feel drawn to most? Has this changed over time, are there techniques/functions/aspects you explore in depth but then grow bored with?

I haven’t really gotten bored with anything yet. It does take time and persistence, but eventually I kind of stumble across new ideas that result in something surprising. Then I try to find ways to exploit those ideas and run with them for a while. For example, I’ve kind of been exploring footwork’ish patterns by using `stut’` in weird ways. It’s a foundational idea that I can put all other strategies on top of. Hopefully other foundational ideas will keep emerging in the future and the strategies will stay fresh with them!

I’ve noticed you put your compositions on github. Is this just out of convenience or something you’ve made a explicit decision to do?

It’s both. I’m slightly paranoid about losing data and code, so GitHub is kind of a backup strategy. However, I’ve always liked sharing my code with others, so GitHub has this nice side effect of making everything available to the public.

I’ve always believed in giving away all of my secrets, whether it’s related to my career or in music. In my entire career I can only think of once when my work was plagiarized. I also just don’t think I have anything to gain by keeping everything to myself. I would love to make more friends in the Tidal world and use it together with more people; sharing my work will only help that.

How does Tidal influence your work, when you are using it do you feel like you are composing, improvising, exploring? Do you feel there’s some expectation for how tidal is used, that you’re going with or against?

When I use Tidal I feel like it is a varying balance of composing, improvising, and exploring. In the studio, it starts with exploring, some grain of an idea, and asking a lot of “what if?” questions. While exploring, I’m looking for something weird or odd that surprises me, or maybe I’m looking to apply a snippet I learned about on the Tidal slack channel. I think during exploration I’m trying to use code I haven’t tried before.

If the result is sonically interesting, then it might become a compositional foundation. I change my approach from code I’m not familiar with to code that can build around the foundational idea.

Improvisation is constant, really. I think one of the powers of Tidal is being able to make a change so quickly and hearing the result. Those “what if” questions can get answered immediately.

I don’t feel like there’s an expectation for how Tidal should be used. I don’t feel constrained in that way. I do feel that there are constraints due to Tidal’s architecture (e.g. a constantly running cycle, discrete events vs continuous events) but not because of an expectation. To me, “expectation” implies that there is a wrong way to use Tidal, and I’ve never felt that at all.

To what extent do you use the standard dirt samples? Do you feel it is important to use your own samples?

I don’t use many of the standard Dirt samples, but not because I don’t like them. I just have a creative desire to design sounds. Often times my sound design process is coupled with the exploratory process of live coding with Tidal. I try to couple an inspiring sound with a bit of new inspiring code.

Many Tidal artists use the standard Dirt samples and the result is an amazing transformation. I think there are nearly infinite creative possibilities in the standard samples.

How does Tidal compare to drumming/other music-making activities/software you have engaged with?

I’ve played drums and percussion since I was 12, and I think Tidal resonates with me because of this. Tidal is such a rhythmic tool and I love it.

I guess I think of Tidal as more of a composition and orchestration tool, whereas drums and percussion are more of a performance instrument. Of course I perform with Tidal, but I am more of a conductor; I orchestrate changes and direct what the parts of the composition are doing. As a percussionist, my concerns are more directed at the performance of a single instrument.

I’ve always liked working with drums in electronic music and creating drum parts that are humanly impossible to play, or that are rhythmically too difficult to “feel”. With traditional music-making software (e.g. DAWs like FL Studio) I would need to place every little note perfectly and it was a tedious process, especially if I wanted to achieve little repetition in the drum patterns. Tidal helps automate this approach and it is very satisfying as a result. I can tell Tidal how to process drums with a few lines of code and it achieves the same thing much more quickly.

How do you see the tidal community/communities in relation to the tidal language? How do you feel about tidal club, has it met your original aim for it, have new aims emerged?

I think the Tidal community and language are tightly coupled. The community has been a huge influence on language features and improvements. We’ve attempted to document Tidal as best we can on the web site, but because live coding is a creative process I think it has been very difficult to convey some concepts through documentation. In-person meetups and online communication are a critical part of spreading knowledge, sharing ideas, suggesting changes, and getting feedback.

And finally a direct but vague question – what do you think Tidal is?

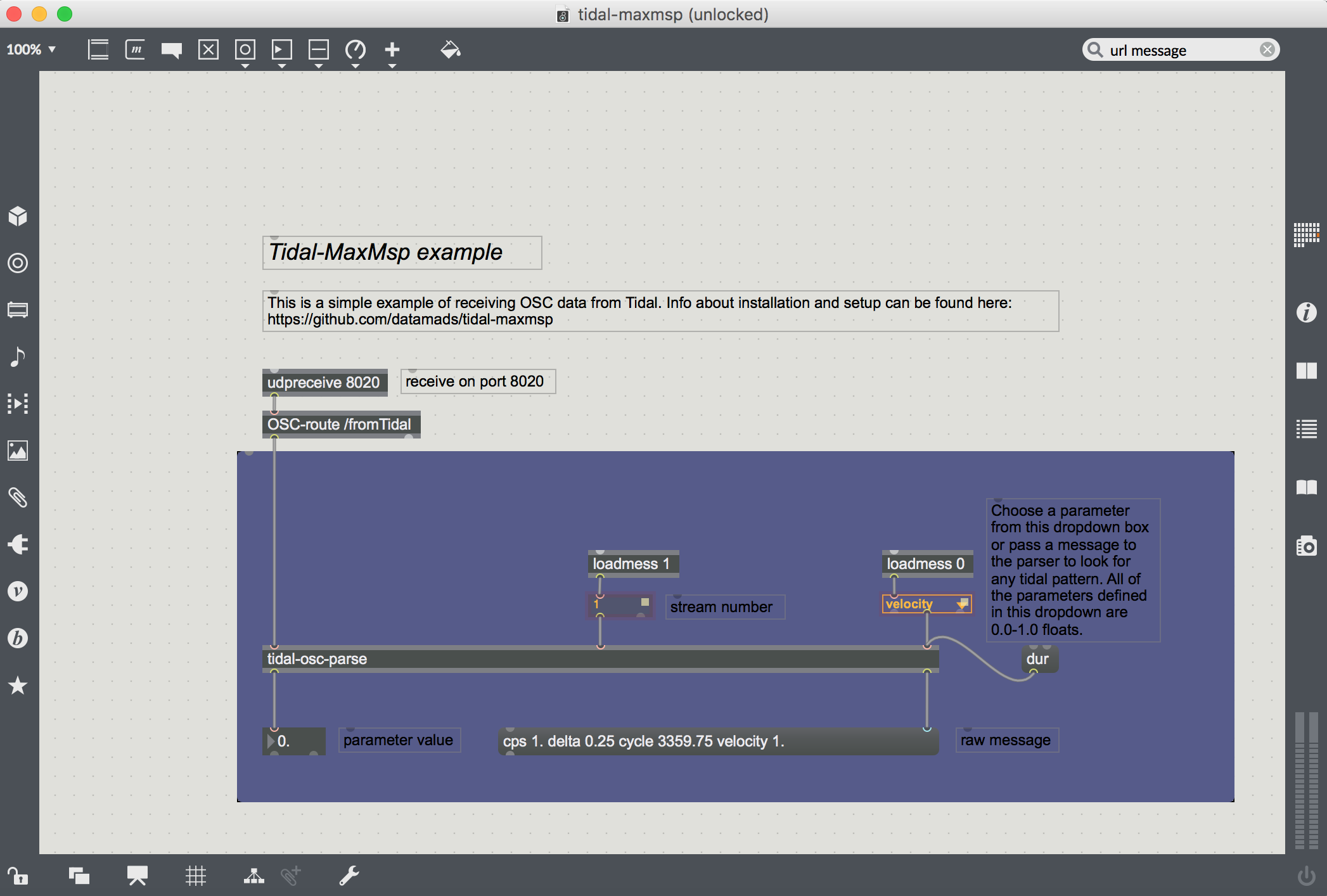

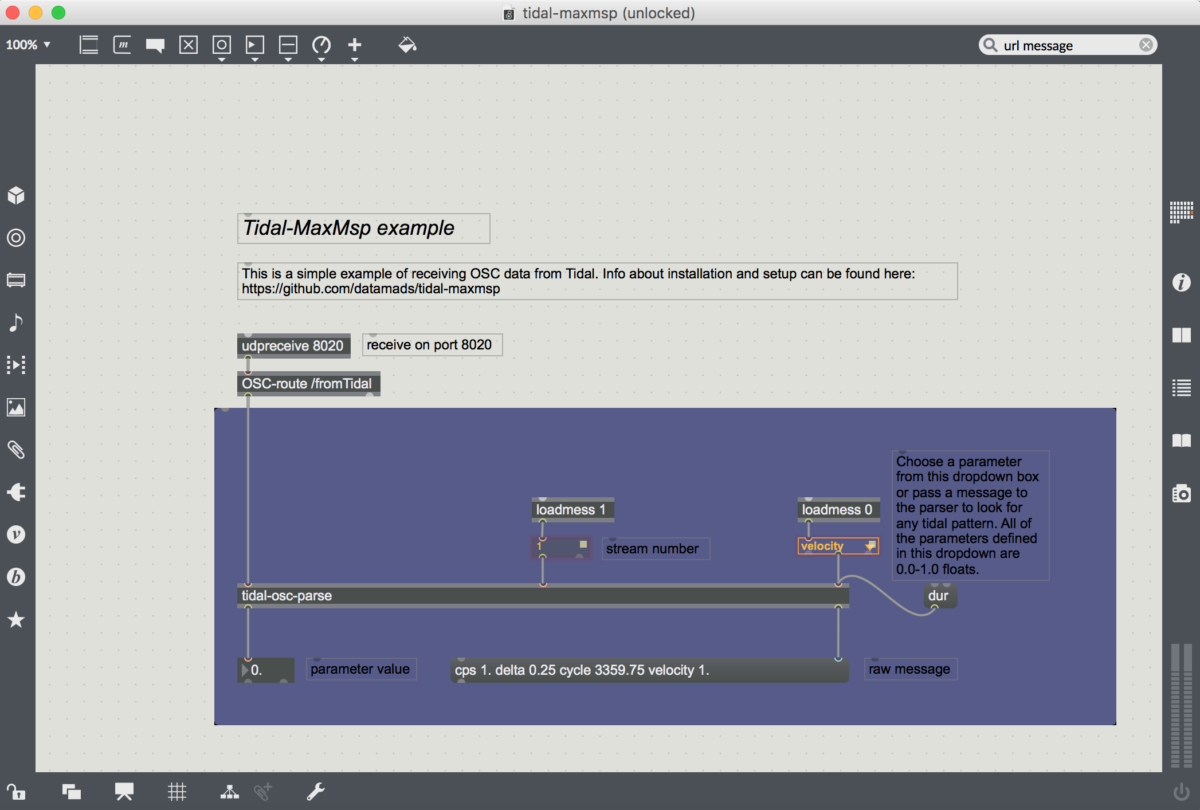

At a very technical level, I think Tidal is a way to express patterns in code. Those patterns can be expressed as data in a file (e.g. an image), messages on a network (e.g. OSC messages to SuperCollider), or whatever else a programmer wants to do with those patterns.

At a more personal level, I think Tidal is the creative tool I’d been trying to find for about half of my life. I wasn’t even sure that I was looking for one. It sparked a creative part of me that I wasn’t sure existed before.

Thanks for sharing!

How does Tidal compare to other music-making activities/software you have engaged with?

How does Tidal compare to other music-making activities/software you have engaged with? How does Tidal influence your work, when you are using it do you feel like you are composing, improvising, exploring?

How does Tidal influence your work, when you are using it do you feel like you are composing, improvising, exploring?